|

|

|

|

Little River Storm G4 Waterblock Review Little River Storm G4 Waterblock Review

|

|

Date Posted: Oct 22 2004

|

|

Author: pHaestus

|

|

|

|

|

Posting Type: Review

|

|

Category: H2O and High End Cooling Reviews

|

|

Page: 1 of 1

|

|

Article Rank:No Rank Yet

Must Log In to Rank This Article

|

|

|

|

|

Note: This is a legacy article, imported from old code. Due to this some items on the page may not function as expected. Links, Colors, and some images may not be set correctly.

|

|

|

Little River Storm G4 Waterblock Review By: pHaestus

|

|

|

Little River Storm G4 Waterblock Review

By: pHaestus 10/22/04

|

|

|

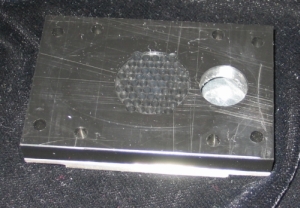

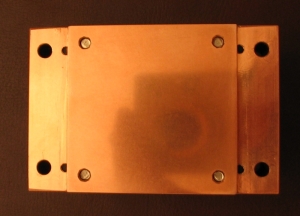

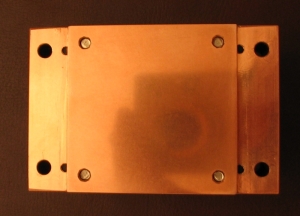

The Storm G4 is the latest waterblock design from Little River Waterblocks. Because Cathar's first two designs (the Whitewater and the Cascade) both set new performance standards upon their release, many liquid cooling enthusiasts have been eagerly awaiting this new block. The

Storm is quite similar to the Cascade in some respects. Both blocks use a copper baseplate with many cups drilled into it, a middle plate with multiple jets (one in the center of

every cup), and a central inlet/single outlet design. The Storm differs from the Cascade in some important ways though. The middle and top plates are black Delrin (which

will not crack), the barbs used on the Storm have a slightly larger inside diameter (and are chrome), the density and size of the cups is changed, and the cups contain a small

pin in their center to increase turbulence. Here's what Cathar had to say about the Storm G4: The Storm G4 is the latest waterblock design from Little River Waterblocks. Because Cathar's first two designs (the Whitewater and the Cascade) both set new performance standards upon their release, many liquid cooling enthusiasts have been eagerly awaiting this new block. The

Storm is quite similar to the Cascade in some respects. Both blocks use a copper baseplate with many cups drilled into it, a middle plate with multiple jets (one in the center of

every cup), and a central inlet/single outlet design. The Storm differs from the Cascade in some important ways though. The middle and top plates are black Delrin (which

will not crack), the barbs used on the Storm have a slightly larger inside diameter (and are chrome), the density and size of the cups is changed, and the cups contain a small

pin in their center to increase turbulence. Here's what Cathar had to say about the Storm G4: |

|

"My objectives were:

- Make a higher performing block than the Cascade

- Make a block that doesn't require as high flow rates to achieve excellent cooling performance, such as would be suitable for use with an

Eheim 1046 and 3/8" ID tubing for which 2-3LPM would be the typical sort of flow rate.

The Storm design is more of a pure-impingement design. The older Cascade design was not strictly a pure impingement design. The jet

width in the Cascade design in comparison to the cup width was too large for a proper jet impingement effect to occur, with the Cascade being more of a "super turbulent mash-in-a-cup" effect. True jet

impingement needs much wider cups in comparison to the jets for the impingement effect to properly develop.

I had experimented with pure-impingement designs both during and after the Cascade design's development with limited success, but

was generally unable to match the Cascade design's strong performance curve over both high and low flow rates. As flow rates got lower, performance of the true jet impingement approach

suffered quite heavily in comparison to the dense high-surface area Cascade approach, and at higher flow rates the true jet impingement approach could at best only match the Cascade design.

I tried a modified impingement approach which forms the basis of the Storm design. The Storm design

implements jet disruptors to turbulate in incoming jets prior to striking the cup's base. The disruptors also offer extra surface area to assist in lower flow applications where the relatively broad cup-base expanse (in

comparison to the Cascade) becomes a liability as thermal convection efficiency falls and the block design then has to rely more upon abundantly available surface area that is easily reached through metal

conduction to sustain good low-flow performance.

The base-plate thickness for the Storm was increased slightly over the Cascade to further assist the pure

impingement approach in lower flow scenarios, but again a balance had to be struck here as today's modern largish CPU dies when covered with an IHS favor a thinner base-plate approach. I strove for the

best balance across what is really a fairly large variation in CPU die sizes, being anything from the bare die ~80mm² AMD CPU's, right up to the >220mm² IHS covered Intel CPU dies. I still wanted to retain high-end

performance for those using pumps strong enough to take full advantage of the Storm design's cooling power

I paid particular attention to the jets for the Storm design, to both optimise the jet intakes in an easily

machinable manner that allowed for minimised pressure loss from accelerating the incoming flow into the jet array, and also offered as close to a one-size-fits-all level of restriction that uses the pump's pressure to

accelerate the water to as high of a velocity as possible, but also without choking flow rates excessively.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Across a very broad range of centrifugal pumps, both actually tested and simulated, the resultant jet velocities are typically around 85-95% of

the maximum jet velocity any commonly used centrifugal water pump can sustain (after other cooling loop pressure drop factors are taken into consideration). It is possible to increase jet velocity further, but the gains are

very small and result in volumetric flow rates falling rapidly which is something that I specifically wanted to avoid because other waterblocks may exist within a user's system which may not act gracefully with a sharp

reduction in volumetric flow rates. With any given pump, jet velocities for the Storm are typically about 1.6x that of what occurs within the Cascade when given the same pump.

In all I feel that I found the best balance that suited the widest range of pumps and system scenarios, while providing the highest level of jet

velocity as it important for the jet impingement effect to work at its best, and also keeping volumetric flow rates high enough to not significantly impact the performance of other blocks in the system." -Stew Forster aka Cathar of Little River Waterblocks

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

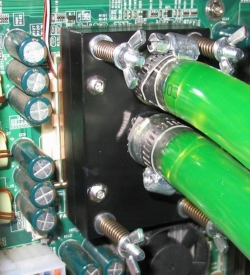

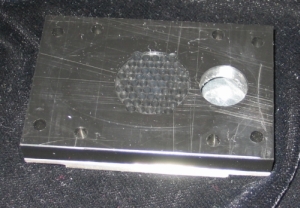

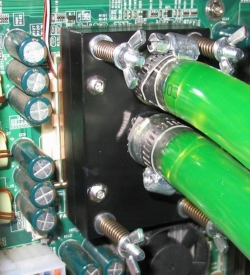

There are several little improvements in the machining and design of the Storm that when combined really improve the overall product.

The stepped base looks nice, the Delrin looks great and is a better choice for the middle and top plates than acrylic, and the chrome barbs and stainless bolts contrast nicely with the black top piece. Little River also includes an adapter plate made of black anodized aluminum (not pictured) that is very well made and looks very nice. The baseplate finish was quite good; no scratches or machining marks could be seen.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Test Results and Observations

|

|

I finally got around to putting together a summary of my testing methods and equipment, so if you want to get the

full lowdown on the Procooling test bench then just give that a read. All testing was done with a TBred B 1700+ at 175x12.5 and 1.825V in bios (estimated to be 71W). Here

is a bit more information on the "delta T" numbers that are used in all the graphs that follow: I finally got around to putting together a summary of my testing methods and equipment, so if you want to get the

full lowdown on the Procooling test bench then just give that a read. All testing was done with a TBred B 1700+ at 175x12.5 and 1.825V in bios (estimated to be 71W). Here

is a bit more information on the "delta T" numbers that are used in all the graphs that follow:

I measure CPU diode temperature, the temperature of the water at the waterblock's inlet, and the water flow rate. By

plotting the difference between CPU temperature and water temperature, we can normalize all testing. This is required because water temperatures may vary from day to day in

my testing room. The closer that this delta T (engineering-speak for temperature differential) is to 0, the better the waterblock is performing.

The first test I conduct is the variation of waterblock performance over many mounting replicates at 1.50GPM flow rate.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Over five mountings the average temperature difference between CPU diode and water inlet was 8.53C, and the standard deviation was 0.15.

There were no problems when mounting this block or in reproducibility of the results.

The next test conducted is the relationship between waterblock performance and flow rate:

|

|

|

|

For comparison the Little River Cascade and Cascade SS waterblocks are also shown.

It is clear from this graph that the cooling effectiveness of the Storm is changed somewhat from the Cascade. At extremely low flow rates (0.25 GPM), the block actually performs worse than the Cascade. As flow rate increases to 0.5-0.75GPM, the performance improved and is essentially equal to the Cascade SS. At flow rates of 1GPM and above the Storm G4's design is superior. Even though the Storm design is more restrictive than the Cascade or Cascade SS, the dT at 1.7GPM for the storm is still around 0.2C better than the Cascade SS at 2.2GPM.

Of interest to most readers is the performance of the Storm G4 waterblock plotted versus other commercial blocks I have tested:

|

|

|

|

The Cascade SS was omitted from this graph because it was made in very small quantities and is no longer available. This figure is getting pretty busy (though

not so much in the Storm G4 region), and I recommend either clicking on the graph or following this link to use Procooling's interactive waterblock comparison page. Despite the number

of blocks on the graph, the Storm G4 is an obvious performance leader over all other commercial blocks at flow rates above 1GPM. At 0.5GPM, the Swiftech MCW6000-A slightly outperforms the Cascade and the Storm, but at

1.00 GPM and above the Storm distances itself clearly from all competition.

The fact that the design of the Storm G4 enables it to outperform the silver Cascade SS is quite surprising and welcome.

Consider that the Cascade SS was AUD$255 and available in very limited quantities. The Storm G4 is AUD$116 and performs as well or better in typical use. It's hard for me to call a US$85 (edited to reflect proper exchange rate) waterblock "a bargain", but if you must have the best-performing waterblock, it just became a lot cheaper.

Thanks again to Cathar for loaning me the Storm G4 for testing.

|

|

|

|

| Random Forum Pic |

|

| From Thread: Home made waterblocks |

|

| | ProCooling Poll: |

| So why the hell not? |

|

I agree!

|

67% 67%

|

|

What?

|

17% 17%

|

|

Hell NO!

|

0% 0%

|

|

Worst Poll Ever.

|

17% 17%

|

Total Votes:18Please Login to Vote!

|

|

Little River Storm G4 Waterblock Review

Little River Storm G4 Waterblock Review

The Storm G4 is the latest waterblock design from Little River Waterblocks. Because Cathar's first two designs (

The Storm G4 is the latest waterblock design from Little River Waterblocks. Because Cathar's first two designs (

I finally got around to putting together a

I finally got around to putting together a